Talking about race is hard, and the conversation is often stifled by White guilt, the fear of making a fatal misstep in language, or the overwhelming weight of historical suffering. White people, even those in a group of friends, can have wildly disparate experiences with race themselves, making dialogue fragile. The only way forward is a shared connection, delivered not through lecture, but through laughter. If I were to create a curriculum for White people to use as a platform to discuss race, I’d use stand-up comedy, mostly with African American comedians, as the primary source.

Humor gives space for insight while we’re distracted with laughing. Satire and irony bypass the immediate emotional defenses we typically deploy when confronted with a lecture on racism. When a critique of police interaction or cultural difference lands—such as those delivered by Mike Goodwin or Roy Wood Jr.—the truth of the insight is already past the mental gatekeeper before the laughter subsides. It allows us to process difficult realities without immediately defaulting to intellectual or emotional resistance.

Humor brings us into community. Laughter is one of the most immediate forms of shared connection. When we laugh at the same truth, even a painful one, we are momentarily united. This shared experience is the bedrock of empathy, which is far more generative than shame. The shared laugh becomes the starting point for a difficult conversation, rather than a fragile hope for one.

Humor showcases Black joy, something that is often missing from discussions of Black life in America. Most media coverage of the Black experience is framed through trauma, struggle, and disparity. Comedy, however, showcases an authentic, powerful, and deeply human existence that is not defined solely by oppression. For White audiences, witnessing this joy, wit, and cultural expression is the key to moving beyond pity or abstract guilt and into a recognition of a complete, resonant humanity. It allows us to learn not just about injustice, but about life.

This is the difference between intellectual awareness and generative empathy. When we allow ourselves to be taught by Black joy and laughter, the task of talking about race ceases to be an obligation driven by guilt and becomes what it should be: a necessary, human conversation driven by genuine connection and the courage to act.

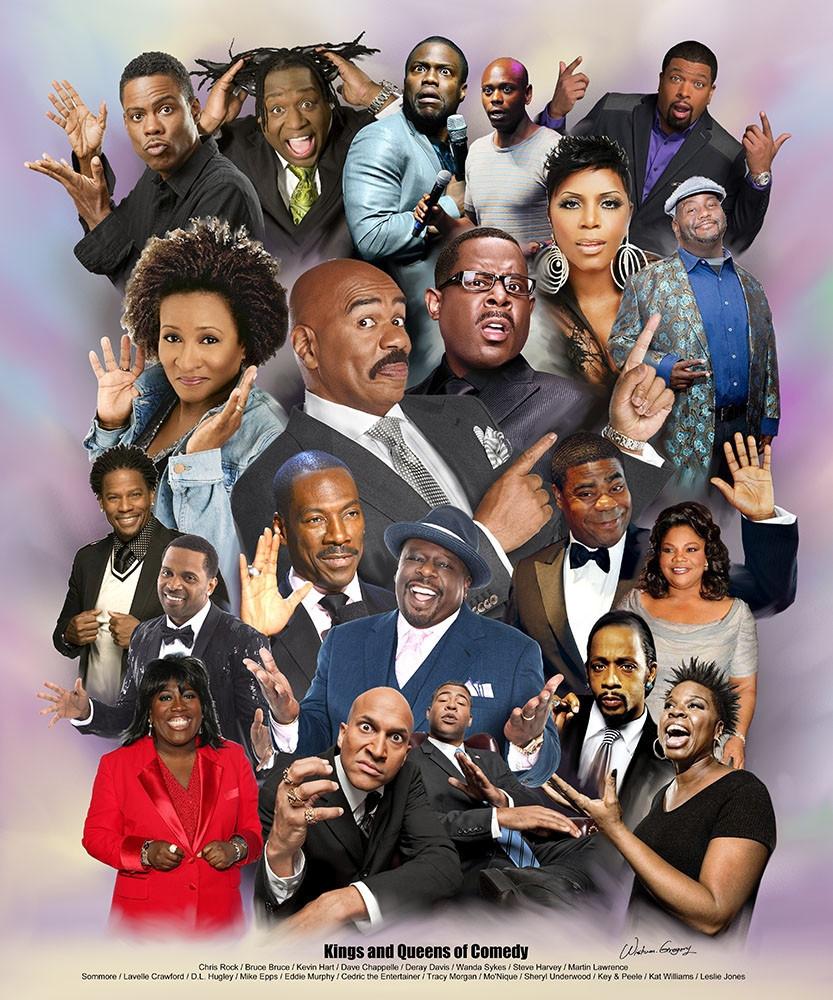

If the courage to act begins with the courage to watch and listen to these lessons, these are the indispensable examples from the masters of the craft. Enjoy:

1. Mike Goodwin: “A Cardigan Is The Perfect Police Repellent”

- Source: A Cardigan Is The Perfect Police Repellent. Mike Goodwin – Full Special

- Key Themes: Goodwin uses his appearance—a well-dressed man in a cardigan—to humorously deconstruct the reality of policing and perception (e.g., “police repellent”). He also touches on cultural moments, Southern idioms, and the uncomfortable history behind terms like “plantation shutters”.

2. Steve Harvey: “Chuuuuch vs. Service”

- Source: Steve Harvey: Chuuuuch vs. Service – You Do Know There is a Difference Right?

- Key Themes: This segment offers a masterful and affectionate contrast between the cultural styles of Black church (“Chuuuuch”) and white church (“Service”). By comparing the emotional energy, prayer reverence, and engagement, he highlights deep-seated cultural differences that extend beyond race and into expression, community, and faith.

3. Roy Wood Jr.: “No One Loves You” (Patriotism Sketch)

- Source: Roy Wood Jr.: No One Loves You – Full Special

- Key Themes: Wood provides sharp political and social commentary on the reality of being Black in America. He reframes the National Anthem debate by calling the U.S. “a restaurant that sells equality” where some have great service and others “need to speak to a manager”. He also touches on police violence, the difficulty of accepting new information, and the different ways Black and White people approach activism and protesting.

4. Gary Owen: “Black Famous”

- Source: Famous in Cincy – Gary Owen Black Famous

- Key Themes: Owen, a white comedian who is divorced from a Black woman and has a strong following in the Black community, uses his unique perspective to contrast general White privilege with “Black Famous” privilege. He explains that being recognized by Black people in customer service roles (like at the airport or rental car counter) allows him to bypass bureaucracy and get hooked up, a humorous reversal of the usual power dynamic found in typical White privilege discussions.

Leave a comment